Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the 32nd president of the United States, came to office at a time of deep crisis for the country. Gone were the ‘Roaring Twenties’ when the country’s total wealth had doubled, and everyone was speculating in the stock market.

The world was in the midst of the Great Depression, and by the time he took his office, 15 million Americans (more than 20 percent of the population) were unemployed, and breadlines and soup kitchens feeding the rising number of homeless people were commonplace.

America was on the brink of collapse. As part of the ‘New Deal’, Roosevelt established the Work Program Administration to administer various job programs meant revitalize the economy. Interestingly one of these job programs was the Federal Art Project where artists were employed to create art that would capture the unique moment in American life.

Why focus on frivolities like art when people are hungry and out of work?

In our times here in Kenya we find ourselves in our own crisis that is threatening our way of life. The economy is spiraling downwards as critical sectors such as tourism and transport have been severely affected by global lockdowns and travel restrictions.

Unemployment is rising as businesses are increasingly unable to wait out the crisis. Our pernicious problem of inequality has become even more acute as the line separating the haves and have-nots becomes a deep valley.

The great equalizer, education, is suspended for the foreseeable future as the majority of children are unable to access learning online, the ramifications of which we may see decades for decades to come. This crisis has the potential to tear apart our social fabric.

Our leaders practised a dangerous game of divisive politics before the pandemic and thus have no playbook for how to keep our society together to see us through to the other side of this crisis. From the lack of adequate public healthcare across the country to the lack of social safety nets, it’s clear that our leaders are ill-equipped to manage the crisis, let alone galvanize the nation together.

It is imperative for the future cohesion of this country that we come out of this period as one nation. In FDR’s dedication of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 1939, he explained that the “[Works Program Administration] artist, in rendering his own impression of things, speaks also for the spirit of his fellow countrymen everywhere. I think the WPA artist exemplifies with great force the essential place which the arts have in a democratic society such as ours.”

Artists have the power to sow our national fabric together and keep our democracy intact. Movies, music, theater, and even new media like animation and games, can speak to our shared fears and pain, hopes and aspirations.

Creators are imperative in helping us imagine a prosperous, equitable, harmonious society post-COVID. This requires both short-term and long-term investment on the part of government, and courage on the part of creators to become the heroes we need.

Art can heal

Although at one point the pandemic seemed to be exclusive to the upper echelons of our society, it is slowly becoming a shared experience as the virus spreads across the country. We are all starting to be affected in one way or another by the restrictions to our normal way of being.

Gathering together, for instance, is an essential cultural norm that has been suspended to manage the spread of the disease. What is Kenyan culture without the regular coming together that we are so used to?

We are all starting to feel the pain of not celebrating together or mourning with our friends as they lose loved ones. While it is true that many are unable to isolate because they need to be out working to earn their daily bread, it is likely that the disease is spreading because we don’t want to stay apart.

As we are locked up in our homes for the safety of our neighbors and loved ones, we need art, broadly speaking, that can speak to the shared pain and anxieties we are feeling.

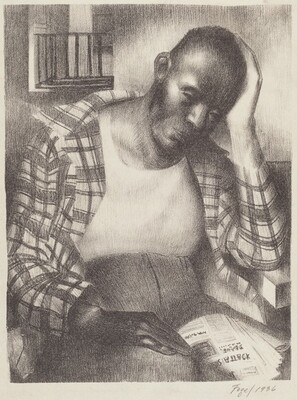

Art is uniquely able to universalize a particular experience by giving its viewers a shared language to express themselves in. In the example of FDR’s WPA artists, they were able to capture the hardship of the period.

Illustrators and photographers perfectly depicted the despair of breadlines and the hopelessness of farms that had been decimated by a severe drought produced by a series of damaging dust storms (much like 2020, everything that could go wrong at the time did).

Seymour Fogel, Untitled (Pensive Black Man), 1936, lithograph.

In the late 1980’s and early 1990’s as the AIDS virus spread rapidly evoking fear and decimating communities, Jonathan Larson wrote Rent, a musical that tells the story of a group of young friends in New York City struggling to find their place in society as the disease took their loved ones. This later inspired Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical Hamilton, a wildly popular hip-hop retelling of America’s founding era.

Hamilton debuted at the end of the Obama era when polarization and social mistrust was at all-time high. It has become a cultural touchpoint enjoyed by Americans of every creed and color as it touches on salient themes like immigration and social mobility. Art can help us heal by reminding us that we are not alone. As the Kenyan adage goes “we are together.”

Art can galvanize

Art also has the unique power to bring a nation together around a common cause. In World War II governments supported, and in many cases, controlled, their creative industry to keep civilians’ morale up and supportive of the war effort. In the U.S.

FDR considered the creative industry so critical to the war effort that Hollywood was asked to consider “how will this picture help us win the war?” Films like the popular classic Casablanca reminded Americans that they were on the right side of the fight, and in the main character, Rick, saw that they were standing up to bullies and protecting the powerless.

These films encouraged personal sacrifice since many commodities like fuel and rubber were being channeled to the war effort. This galvanizing effect was not just seen in the film; musicians and dancers were hired by the United Service Organization (USO) to perform popular music of the time like swing and jazz for citizens and troops stationed overseas.

Even comic book characters like Superman and Batman, and animations like Bugs Bunny, Tom and Jerry, were enlisted to the war effort. For troops and the nation the message of this art was the same, “we’re winning the war and you’re helping us do it.”

In our own context we have used art to galvanize our communities towards a common cause. Mwomboko was a Neo-traditional dance popular with the Agikuyu, one of Kenya’s 42 tribes, that disguised itself as an indigenous version of the waltz.

Mugithi music is a style of music also that mixes traditional sound with modern instruments. Rebels used it to pass messages and rally to the anti-colonial cause. In a time of turmoil and conflict, this music and dance asserted pride in the culture and encouraged the community to move and work together as one.

A personal favorite, ‘Mwene Nyaga’, recorded most recently by Kwame Rígíi, is a stirring war song said to have been sung by the Mau Mau, Agikuyu resistance group that fought for independence . Although it is not sung in my mother tongue, the themes in the song are universal to Kenyans: the desire for togetherness, a deep connection to land and place, a reverence for the divine, and an appeal for said divine to help us overcome a common challenge.

Let’s get a New Deal

The arts and access to them are essential for a robust thriving society. Roosevelt believed that art would foster resilience and pride in American culture and history. WPA artists were not given any requirements in subject and style as it was expected that the art would be an accurate reflection of the place it was created and that it would be accessible publicly.

According to the National Gallery of Art (USA) “public murals were painted for display in post offices, schools, airports, housing developments, and other government buildings…The WPA intentionally seeded arts programs and supported artists outside of urban centers.

In so doing, it introduced the arts to a much more diverse swath of Americans, many of whom had previously never seen an original painting or work of art, had not met a professional artist, nor experimented with art making.”

As our government develops strategies to rebuild our economy, it will be essential that cultural production is included as a key driver of recovery. It was commendable that the government found resources to support artists to create COVID-19 related content. Although the 100 million KSH (1 million USD) did not go a long way, it demonstrated an understanding of the essential-ism of cultural production to our stability.

We need to do more to take music, painting, dance, film, and photography all across the country to capture this unique moment in history, to show us that we are more alike than we are different. Art has a critical role to play during this crisis to define for us who we are, what we value collectively, and what we’re trying to be.

Artists of every persuasion can help us move past the cynical ‘us versus them’ politics that drives social division at the will of a few power hungry actors. In the fight that we’re in there is only ‘all of us’ versus the invisible but very dangerous enemy. This of course requires courage on the part of artists to move past cynicism to give us a vision of what we can be as a nation.

Unfortunately much of our art today seems to be stuck in this cynicism. Kenyan hip hop artist King Kaka’s ‘Wajinga Nyinyi’ is important in that it holds up a mirror to our society, but doesn’t, in my view, add anything to our national conversation — many people already believe we pick bad leaders.

Michael Soi, a Nairobi based artist, paints pieces that are captivating and irreverent, but show little hope and optimism. Artists have been blessed with the gift of vision — they have an ability to create what we have never seen. What are we striving for? What does a Kenya without corruption look, sound, and feel like? What can artists create that will make us feel proud to be Kenyan?

What can encourage us to take care of ourselves and each other, and to sacrifice for the greater good? The values we emphasize during this crisis will define this time in our collective psyche and will make or break us as we seek to rebuild or re-imagine a new normal.

Roosevelt’s Federal Art Program ended in 1943 at the onset of World War II but by that time the program had mainstream public art. Artists had meaningful work, making art for ordinary Americans. The triumph of the program is that it gave a vision of a new inclusive America where women and African Americans had more access to opportunities.

What does an inclusive future look like for Kenya? The artists can show us.

This article was first published on Marketing Africa.